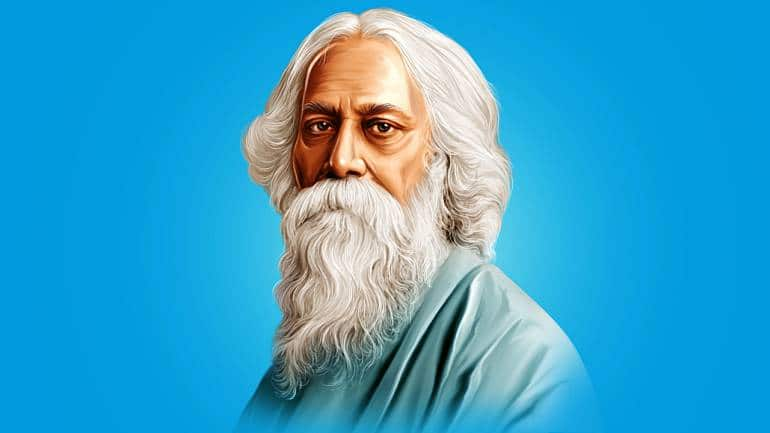

|| Rabindra Jayanti || Special By Meghna Roy

Voice of Bengal

Rabindranath Tagore, who died in 1941 at the age of eighty, is a towering figure in the millennium-old literature of Bengal. Anyone who becomes familiar with this large and flourishing tradition will be impressed by the power of Tagore’s presence in Bangladesh and in India. His poetry as well as his novels, short stories, and essays are very widely read, and the songs he composed reverberate around the eastern part of India and throughout Bangladesh.

The contrast between Tagore’s commanding presence in Bengali literature and culture, and his near-total eclipse in the rest of the world, is perhaps less interesting than the distinction between the view of Tagore as a deeply relevant and many-sided contemporary thinker in Bangladesh and India, and his image in the West as a repetitive and remote spiritualist. Graham Greene had, in fact, gone on to explain that he associated Tagore “with what Chesterton calls ‘the bright pebbly eyes’ of the Theosophists.” Certainly, an air of mysticism played some part in the “selling” of Rabindranath Tagore to the West by Yeats, Ezra Pound, and his other early champions. Even Anna Akhmatova, one of Tagore’s few later admirers (who translated his poems into Russian in the mid-1960s), talks of “that mighty flow of poetry which takes its strength from Hinduism as from the Ganges, and is called Rabindranath Tagore.”

Rabindranath did come from a Hindu family – one of the landed gentry who owned estates mostly in what is now Bangladesh. But whatever wisdom there might be in Akhmatova’s invoking of Hinduism and the Ganges, it did not prevent the largely Muslim citizens of Bangladesh from having a deep sense of identity with Tagore and his ideas. Nor did it stop the newly independent Bangladesh from choosing one of Tagore’s songs – the “Amar Sonar Bangla” which means “my golden Bengal” – as its national anthem. This must be very confusing to those who see the contemporary world as a “clash of civilizations” – with “the Muslim civilization,” “the Hindu civilization,” and “the Western civilization,” each forcefully confronting the others. They would also be confused by Rabindranath Tagore’s own description of his Bengali family as the product of “a confluence of three cultures: Hindu, Mohammedan, and British”. Rabindranath’s grandfather, Dwarkanath, was well known for his command of Arabic and Persian, and Rabindranath grew up in a family atmosphere in which a deep knowledge of Sanskrit and ancient Hindu texts was combined with an understanding of Islamic traditions as well as Persian literature. It is not so much that Rabindranath tried to produce – or had an interest in producing – a “synthesis” of the different religions (as the great Mughal emperor Akbar tried hard to achieve) as that his outlook was persistently non-sectarian, and his writings – some two hundred books – show the influence of different parts of the Indian cultural background as well as of the rest of the world. Most of his work was written at Santiniketan (Abode of Peace), the small town that grew around the school he founded in Bengal in 1901, and he not only conceived there an imaginative and innovative system of education, but through his writings and his influence on students and teachers, he was able to use the school as a base from which he could take a major part in India’s social, political, and cultural movements.